The Importance of Balance in Riding: The Meeting Point of Horse and Rider

A correct position is far more than good posture: it is the essential foundation of effective, safe, and horse-friendly riding. Balance in riding represents the true meeting point between horse and rider—an invisible space where their movements merge and become a single, harmonious gesture. Understanding how balance works in riding means laying the groundwork for clear communication, precise aids, and technical progression that supports the partnership from the earliest stages through to advanced levels.

In equestrianism, three distinct yet closely interconnected forms of balance come into play: the horse’s natural balance, the rider’s balance, and the balance that results from the level of training. Ignoring even one of these compromises the quality of the work, alters the gaits, and over time increases the risk of stiffness, technical faults, and unnecessary strain.

The Horse’s Natural Center of Gravity

When the horse is standing still, its center of gravity is located approximately midway between the withers and the abdomen, beneath the saddle panels and close to the girth area. In this static condition, weight distribution is not even: about 60% is carried on the forehand, while 40% rests on the hindquarters. In particularly powerful or heavy-built horses, this proportion can shift to as much as 66% in front and 33% behind.

It is essential to understand that, unlike some other animals, the horse has a relatively rigid spine. As a result, during movement its center of gravity shifts only to a limited extent. In the gallop of a racehorse, for example, the center of gravity tends to move even further forward, especially during phases of maximum propulsion. In dressage, by contrast, a well-trained horse progressively learns to transfer a greater percentage of its weight onto the hindquarters, sometimes exceeding 50%.

This redistribution is not natural but the result of correct, gradual training aimed at making the horse more weight-bearing behind, more balanced, and lighter in front.

The Rider’s Influence on the Center of Gravity

With a rider in the saddle, the combined center of gravity of the partnership rises by about 10% compared to that of the horse alone, while remaining on the same vertical line. This fact is often underestimated, yet it has a significant impact on overall balance. The rider’s weight must not disrupt the horse’s natural load distribution on the limbs, otherwise the gaits and fluidity of movement are compromised.

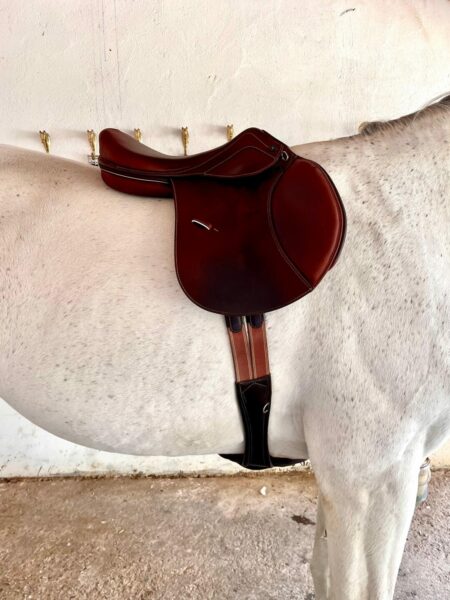

How the rider sits determines where and how this weight is transmitted to the horse. A light, forward seat typical of show jumping shifts much of the weight onto the legs and stirrups. Since the stirrup bars are positioned near the front arch of the saddle, the load tends to concentrate around the withers, increasing pressure on the front part of the back.

A well-fitted saddle can help distribute weight over a larger surface, but it cannot compensate for an incorrect or unbalanced position. Ultimately, it is the rider—before the equipment—who must consciously manage their own balance.

Balance and Discipline: Dressage and Show Jumping Compared

Every equestrian discipline requires a specific position, all built around the same fundamental principle: harmony with the horse’s movement. In dressage, the rider’s weight is primarily in the saddle, with longer stirrups that encourage a deep seat. Balance is managed mainly through the pelvis, maintaining alignment of shoulders, hips, and heels.

In show jumping, by contrast, the seat is light, the weight is carried through the legs, and the stirrups are shorter. Balance is maintained by loading the shins, with knees and forefeet correctly aligned. In both cases, the objective remains the same: not to interfere with the horse’s balance, but to accompany it.

Empathy, Perception, and Communication

Balanced riding is not merely a mechanical issue. It requires empathy and the ability to perceive the horse’s movements, understand its reactions, and adapt continuously. The rider must develop the sensitivity to feel when the horse loses balance, stiffens through the back, or, conversely, moves with looseness and fluidity.

Only through this awareness can the aids be transformed into a true shared language. This is the moment when the rider stops being a mere passenger and becomes an active partner, capable of guiding the horse without forcing it.

In the second part, we will examine how position directly affects balance on curves, the correct placement of the saddle, and the fundamental role of training in transforming a “level” horse into one that appears to move “uphill.”

Source Manuale Completo di Equitazione by William Micklem

Ph Stefano Secchi

© Rights Reserved.